- Home

- Jackie Lea Sommers

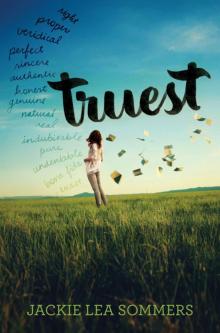

Truest

Truest Read online

Dedication

For Emma, Ava, Elsie, and Owen, four PKs I love even more than Westlin Beck.

And also for Cindy Woerner, whose conversations fueled this story, and for Kristin Luehr, who rescued it twice.

Contents

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Acknowledgments

Back Ad

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

one

The swans on Green Lake looked like tiny icebergs, only it was the first weekend of my summer vacation. One hundred feet from where I sat in the car, they lay quiet claim to the lake, as if it were their inheritance.

“Here? Really? I thought we were going to Gordon’s,” I accused, now staring out the windshield from the passenger’s seat at the sprawling Tudor-style home that was definitely not the senior living center.

“We are,” Dad said. “After this.” He rooted around in the backseat for his portable communion set, a black leather case with “In Remembrance” embossed on the cover in gold. “Ready?”

“Can I stay in the car?”

“West,” my dad said, his voice thick with disapproval. I grumbled as I undid my seat belt.

At the front door, Dad rang the doorbell. Inside, a voice yelled, “Got it!” After the sound of approaching footsteps, the door opened, and in its frame stood a boy my age.

He was tall—maybe six foot two or three—and thin, with a perfect jawline and beautiful peach lips. His hair was a thick, dark mop that fell into his cheerful eyes. They looked at my dad expectantly, as if he’d come a-caroling.

Then he saw me.

In an instant, he went from ten-thousand-watt cheer to shadowy disappointment. My ears grew hot in humiliation. Did I have something in my teeth? I ran my tongue over them to check—all good.

Dad was as distracted as ever and noticed none of it. “Hey there. You must be Silas,” he said, shaking the boy’s hand. “Pastor Kerry Beck. This is my daughter West.” I offered a little wave, but he ignored me.

“Good to meet you, sir,” said Silas, the smile returning—and seeming genuine enough—for my father. He held the door open for us, saying, “Come on in. Mom! Dad!”

As I walked in past him, he dropped his gaze, refusing to even look at me. His threadbare T-shirt read, “PRACTICE SAFE LUNCH: Use a Condiment.” It seemed completely out of place inside this storybook house.

“Sunroom is this way,” he said, leading me and Dad down a hallway, past the kitchen, and through the dining and living rooms, which were being updated to modern perfection. Thomas and Joanie Griggs, the former occupants, had called it quits on Minnesota winters and moved south two or three years ago. Rumor had it “the old Griggs house” had a rooftop patio with a fire pit the size of a hot tub.

A rich house for rich snobs, apparently—I’d expect nothing less from Heaton Ridge, the expensive thumb of our mitten-shaped town.

Anyway, why should I care if the hot new guy was a jerk? I had a boyfriend.

Still, Silas’s obvious disappointment irritated me. What had he been expecting?

The sunroom turned out to be more like a conservatory—glass-paned walls and ceiling, vaulted and with white beams. This house couldn’t have been more different from our family’s humble little parsonage. A white rug made of something suspiciously like polar bear fur covered the pale floor and lay beneath a matching set of white wicker furniture. Sitting on the couch was a princess.

I stared. The girl, who also looked about my age, offered only a faint smile as we entered the room. Her hair was the color of golden honey, and with the afternoon sun shining down through the glass ceiling, she glowed like an angel. She had the same perfect peach lips as Silas (a sister, I realized), beautiful cheekbones, dramatic eyebrows, and a pale oval face. It took me several moments to notice she was wearing her pajamas.

“Hi, Pastor Beck,” said a man, stepping from behind us into the sunroom along with his wife. He nodded toward his daughter. “This here is—”

“Laurel,” said the girl, holding out her hand to shake my father’s, although she made no move to stand up. She turned toward me. “Hi,” she said, still only the slightest of smiles on her face. Her eyes looked deep into mine, not unkindly—but fierce. And only for a moment. Then they seemed to fade somehow, as if a light inside her had turned off.

It gave me goose bumps.

“West,” I muttered. “Nice to meet you.”

Everything was too quiet in this eerie glass room—but then a hand on my shoulder broke the tension. “West, good to meet you,” their mom said. “Teresa Hart. This is my husband, Glen.” Noticing Silas’s T-shirt, she rolled her eyes. “You couldn’t have changed?” Silas laughed and kissed his mom on the cheek, making her grin. “Silas, go show West around.”

I glanced at my dad, hoping he’d object—after all, he had strict rules about when and where my boyfriend, Elliot, was allowed in our house—but he only smiled in a have fun sort of way. Silas looked as horrified as I felt, and that pissed me off even more.

“We can just stay . . . ,” Silas began, but his mother said, “Shoo.”

Annoyed, he nodded in the direction we’d come from. Great. He wasn’t even going to speak to me.

The carpet that lined the stairs was thick, luxurious. Every step felt like this—family—is—so—rich. I asked, “So, how long have you guys been in Green Lake?”

He sighed, and for a second I thought maybe he’d just ignore me. But then he said, “Couple weeks? We moved from Fairbanks.”

“Alaska?” I asked, dumbfounded. “Why’d you move to Minnesota?”

“My mom grew up here.” We passed an open door, the second on the left. “This is my room.”

I paused in the doorway. The room smelled like boy—and a little like feet, which I assumed came from the beat-up Nikes that were tucked halfway under the bed. It was messy inside, a welcome respite from the perfection of everything else I’d seen—some shirts and jeans lying on the floor, and a pair of boxers, from which I quickly looked away. A song I didn’t know was playing from an ancient CD player, and there was a small TV in the corner of the room. Beside the TV was an empty frozen-pizza box with some pieces of crust on it. Silas’s nightstand was piled high with a mix of Runner’s World magazines, notebooks, and novels. Beside his closet was a huge bookcase, double-lined with books.

“You wanna see the roof?” he mumbled from the doorway, looking in on the chaos.

But I was in his room already, the bookcase drawing me in like a tractor beam, my hand automatically reaching for the spines. Rather, reaching for a spine—Collier by Donovan Trick, my favorite book, favorite writer. I pulled it off the shelf, noticing the telltale signs of devotion: well-worn cover, cracked spine, three or four makeshift bookmarks marking favorite pages.

“Is this y—?” I started to ask.

“Be right back,” he mutter

ed before disappearing down the hall.

“Um,” I said aloud to no one, “okay.”

Being alone in his bedroom was awkward, but I wasn’t sure where else to go in this unfamiliar house. I looked down at the book in my hands and opened it; there was an inscription on the inside cover.

Silas,

“Stories are our most august arms against the darkness.”

We know you know that.

Love, Mom and Dad

Silas slipped back into the room. “Do you listen to August Arms?” I asked, turning to look at him. His hair was all wet, and his T-shirt was soaked around the collar.

“Is that a band?” he asked, looking everywhere around the room but at me.

“No, it’s a radio show I like.” I put the book back. “Are you okay?”

“I’m fine. You read much?” Silas asked, sitting down on the edge of his bed. Posters hung on the wall behind it. One said “NOTICE” in official-looking red letters across the top, and beneath it were the words “Thank you for noticing this notice. Your noting it has been noted.” Beside it was a poster of an orange looking in horror at a glass of orange juice and saying, “Mom??” In the corner of the room was a full-sized cardboard cutout of Darth Vader.

Silas followed my gaze. “At night, Vader joins me in bed and puts his head on my chest,” he joked. “Falling asleep to the sound of his ventilated breathing is very soothing, actually.”

“I’ll bet,” I said dryly. I hadn’t answered his question—nor was I going to. What business was it of his whether I “read much”? And why were his hair and shirt all wet? Why the jokes after he’d been so unapproachable? I couldn’t nail down his mood.

“Poetry’s my thing, I guess,” he offered.

“You read poetry?” I asked, narrowing my eyes in skepticism.

“‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,’” he said, like a total asshat.

“Enchanting,” I said.

“I’m not just being a tool,” Silas said. “Shelley wrote that.” He paused, then added, “The English Romantic poet?”

“I know who he is,” I said. Well, I sort of knew who he was, at least.

Then, in the most baffling move in the history of mankind, Silas grinned—that same goofy, cheerful grin I’d seen at the front door—and my heart turned a traitorous cartwheel.

I had to look away.

I struggled to regain the ground I’d lost to that grin. Faking confidence, I sat down beside him, then immediately doubted myself but tried not to show it. “So what’s with Laurel?” I asked, careful not to let my shoulder get too near to his. “Can she walk?”

He frowned. He had a tiny freckle on his left cheek. “Yes. She’s fine.”

“Oh,” I said, retreating. “Sorry. We just usually bring communion to—sorry. I thought that maybe she—”

“She’s fine,” he repeated with a scowl. “Small towns,” he spat out, then bit back whatever he was going to say next.

“I should go,” I said, starting to get up.

“No, don’t.” He clutched my shoulder so that I stayed seated. I wrenched it away from him. “Sorry,” he mumbled.

I glared at him, and he seemed to soften. “Sorry,” he said again, his mouth a worried knot until he maneuvered it into a forced smile. “Laurel—she’s my twin sister. It was really good of your dad—and you—to bring over communion. Body and the Blood. Good conversation.”

“Conversation?” I asked. “With my dad?”

“With God,” he said, without explanation.

I’d never thought of it that way before. To me, it tasted like crackers and juice.

“How old are you?” I asked him, suspiciously. No one my age talked that way.

“Seventeen. You?”

“Seventeen.”

I looked hard at Silas Hart. His cheekbones were like Laurel’s, his eyebrows aggressive and his eyes just as alive as his sister’s had looked hollow. “What?” he asked, but this time his voice had a playful, almost teasing, tone. He knocked his knee against mine.

“Nothing,” I said, standing up and moving away from him. On the other side of the room, I leaned my back against his bookcase. “Your mom grew up here?”

“Yeah, Teresa Mayhew, if that means anything to you. My grandparents are—”

“Arty and Lillian?”

“Yeah. Wow.”

I shrugged. “They sit behind us in church. Your grandpa gives out gum to the Sunday school kids. Your grandma . . . is usually upset over something.”

Silas laughed. “Sounds about right.”

“Here’s your first lesson in small town life: every last name means something. Thomas means you’re adopted; Boggs, you’re homeschooled; Travers, you raise cattle. Arty and Lil are the only Mayhews still around, but the name still has a reputation for being athletic.”

Silas raised his eyebrows. “My mom and aunt were both state track stars. That’s actually a little creepy, you know.”

“It’s Green Lake.”

“Wink!” my dad called up the stairs. “Ready to go?”

Yes.

No.

Maybe?

“Coming!”

Silas followed me out, asking, “Did he just call you ‘Wink’?”

I ignored him.

At the bottom of the stairs, Mr. and Mrs. Hart were saying good-bye to my dad. I glanced back down the hall in the direction of the sunroom, wanting to see Laurel again, but the couch was now empty.

“Silas, good to meet you today. We’ll see you at church next week?” asked my dad, shaking Silas’s hand again.

“Yes, sir,” Silas promised with a grin, “or I’ll have Oma Lil to answer to.”

He was charming my father, who laughed and said, “Nobody wants that! Glad you got to meet Westlin. Maybe she can show you what’s fun in Green Lake.”

“There’s nothing fun in Green Lake,” I countered. Then I smiled at Mrs. Hart to show her I was joking, even though I wasn’t.

“Actually, I need to find a decent summer job,” Silas said. “No fun for me.”

“West here makes pretty good money detailing cars in the summer, and she’s short a business partner and needing some help,” my dad said. His words were a double blow: first, a bitter reminder that my best friend, Trudy, had left just yesterday, abandoning me for summer camp; and second, Dad’s offer to Silas to take her place. I glared at Dad—but only for a second. Pastors’ kids aren’t supposed to glare.

Silas looked equally reluctant, but Dad said, “A divine appointment!”

How do you tell the pastor to shut the hell up?

He and Mr. and Mrs. Hart all looked at me.

“You interested?” I squeaked out against my will.

“Sure,” Silas said, sounding anything but.

“Okay, well, I have a detailing tomorrow morning at nine. We’re in the parsonage by the community church. You should wear junky clothes.”

Silas pointed to his condiments T-shirt with a smirk. “I’ll be there at five to.”

two

After the calamitous transaction with Silas, I gave my dad the silent treatment all the way to Legacy House, though he never seemed to notice. But my mood changed when Gordon answered his apartment door. Dark glasses on, he looked like an elderly Ray Charles with an even brighter smile.

“Welcome, welcome, Pastor Beck!” he said. “West? You there?”

“I’m here, Gordon.” I tugged gently on his sleeve. Gordon is, among many things, blind, ninety-something, and, as a retired university professor, the smartest man I know. I’m pretty sure his doctorate was in American history, but as far as I’m concerned, he has a PhD in Everything.

“Come on in,” his warm voice welcomed us, then he walked confidently—though a little stooped—back into his living room and sat down in his rocker, turning off his radio on the way, which was—as always—tuned to the station that hosted August Arms. The whole room smelled like cherry pipe tobacco and peppermints, the latter of which Gordon

kept in tiny bowls all over the apartment. I helped myself to one.

Gordon lives in the “senior apartments” half of Legacy House meant for those who manage mostly on their own. The other half is for assisted living—smaller rooms, a twenty-four-hour nursing staff, and a lot less freedom. I didn’t like to think of Gordon moving to the other side, though Dad said it was only a matter of time.

Gordon’s apartment is one of my favorite places: everything is always in its perfect spot, which allows him to move around freely—the couch, the coffee table, Gordon’s own rocker—and the walls have no decorations. Our house, the parsonage next to the church building, looks like Pinterest barfed all over it.

Instead, Gordon’s walls are lined with bookcases.

“How have you been, Gordon?” my dad asked, his upbeat voice not matching the tired look on his face. He set his little portable communion set on the coffee table and opened it up, taking out the container of grape juice and pouring some into a tiny disposable cup.

“I’m going to snoop around your shelves, Gordon, okay?” I said, standing up and walking to the nearest bookcase—a colossal mahogany one that seemed to house at least twenty Steinbeck novels, along with a collection of books about military weaponry.

“Oh, sure, sure, Westie. Help yourself. Always learning, Pastor Beck. Always learning,” Gordon said as my dad took the older man’s dark hands, opened them, and placed a cup in one and a wafer in the other. “Just started teaching myself Spanish online. And listening to the Narnia CDs my great-granddaughter bought for me. Always dreaming about heaven and seeing Mavis again. El señor, prisa el día.” Gordon raised the miniature cup as if he were toasting God, then put it to his lips. He ate the bread and was silent for a moment.

Dad’s cell phone rang. He looked at it. “Oh, I’m so sorry, Gordon. I’ll just take this in the hallway.”

Gordon was unfazed. He began packing and lighting his pipe with a practiced hand, putting out the match in a little jar of water. He drew on his pipe, then let out the cherry-scented smoke, asking, “Westie, will I see you much this summer? I mean, of course, figuratively.”

I laughed and turned from where I was running my fingers over the spines of the books. One of my teachers had told me East of Eden was a must-read. “Of course! You can’t get rid of me.”

Truest

Truest