- Home

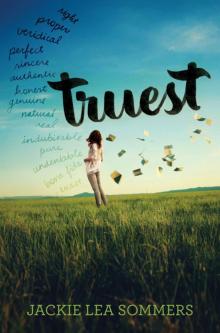

- Jackie Lea Sommers

Truest Page 2

Truest Read online

Page 2

“Nor would I want to,” he said, grinning. “Car detailing again this summer?”

“I guess,” I said, my voice withering. “Trudy bailed on me to be a counselor-in-training at an adrenaline junkie camp in Wisconsin,” I groused, pulling East of Eden off the shelf.

I pictured us in summers past: detailing cars and talking about all the things we couldn’t with anyone else, like ghosts and periods and whether our friend Whit was drinking too much since his dad died. We grew up together, me and Trudy. My mom did day care for her when we were little, so she was sort of like my first sister, before my actual sister, Libby, came along. Tru and I spent those early years building castles in the sandbox and making up plays and organizing the church hymnals in exchange for candy money. We were never ones to be athletic, and our parents were politely asked to withdraw us from T-ball when we made a habit of making dandelion chains in the outfield instead of watching for fly balls.

Trudy and I were the least likely candidates to spend a summer at adventure camp, so when she told me about her plans, it felt like a betrayal. We rarely fought—barring the incident when we were four and she sat under the kitchen table, systematically breaking my crayons—and even though this wasn’t a fight per se, her absence hurt me. A lot.

Before Gordon asked any more questions, I added, “Not only that, but Elliot’s dad hired him on at the farm, so it’s like he’s gone, too. And”—I lowered my voice, even though I knew Dad couldn’t hear me from the hall—“now Dad brokered some partnership with this moody new kid in town. It’s just not how I pictured this summer going. Can I borrow East of Eden?”

“Thou mayest,” he said, which didn’t make sense until a few days later, when I’d read most of the book. “And haven’t you learned anything from August Arms and all your reading, Westie?” Gordon asked. “With a setup like that—static in the air?—lightning is bound to strike.”

That evening, I took the family car out to the Thomas farm to see Elliot. There are six Thomas kids, all adopted from the Philippines, and all but Tara—Elliot’s oldest sister who was in college and studying abroad for the summer—were always running around the farm in pleasant chaos.

Lorelei and Laney, the two youngest at five and seven, mobbed me when I stepped out of the car. “Did you come to babysit?” Lorelei asked. “Why didn’t you bring Libby?”

“Let’s make popcorn!” added Laney. “With Red Hots!”

I gave them both hugs. “I think it’s almost your bedtime. Where’s Elliot?”

Greg, thirteen, pulled up on a four-wheeler. “Elliot’s inside showering; he just finished milking.”

“Mom’s inside too!” said Lorelei, taking one of my hands. Laney grabbed the other, and the two of them ushered me indoors.

“Elliot!” Laney shouted down the stairs to her brother. “West is here—but she’s not babysitting and didn’t bring Libby and won’t make popcorn!”

I giggled as they dragged me into the kitchen, where their mother was. “Hi, Mrs. Thomas!” I said. She had been my sixth-grade teacher, and I’d never gotten used to calling her anything else.

“West!” she said, wiping up flour from the island, where she’d been making bread. “So good to see you! Enjoying the first weekend of summer?”

I pulled a stool up to the island and paused before I answered.

She laughed. “I know, I know—it’d be a lot easier if Elliot wasn’t working full-time for his dad, right?”

“Bingo.”

“I heard there was a pretty girl upstairs,” Elliot said, appearing in the kitchen doorway, his hair wet and his T-shirt clinging to him. His little sisters giggled, one on either side of me. I had been dating Elliot for nearly two years—to the town, he was a football god; to me, an unassuming boyfriend, modest and mellow in spite of the attention lavished on him for years.

“There is,” I answered. “Your mom’s a total knockout.”

Mrs. Thomas rolled her eyes and shooed us out of the kitchen.

Elliot and I went downstairs to his bedroom, stunningly clean in comparison to Silas’s—and, admittedly, my own. Elliot lay on his back on his bed, and I lay on my stomach beside him.

He and I have known each other forever. In second grade we got “married” under the monkey bars at recess—or would have, anyway, if Mark Whitby hadn’t tattled on us, making the playground attendants come over and break things up before we’d kissed. Still, I did make off with the ring he’d gotten from a gumball machine, and wore it for at least a week before it turned my finger green.

I still kept the ring—cheap, soft metal etched to give the illusion of sparkle—in the desk drawer in my room, though I hadn’t taken it out since the night sophomore year when Elliot had finally kissed me at the end of Trudy’s dock, eight years after a young playground “minister” had pronounced us husband and wife. I’d tried it on again that night, and since it was one-size-fits-all, I had to widen it only a little to make it fit.

“How was your day?” he asked now, his head turned toward me.

“You are not going to believe this,” I said, picking at my nail polish, which was chipping off, “but Dad found a detailing partner for me today, and he’s kind of an asshole.”

“Wait, what? Who?”

I grinned at the barrage of questions. “Silas Hart. He’s new to town. His mom is Arty and Lillian Mayhew’s daughter.”

“Holy shit, really? I think my dad dated her in high school.”

“No way.”

“I think so. Teresa?”

I nodded. “Well, she’s back,” I said, “and she brought her kids with—they’re in our grade. Silas is really . . . moody or something, and Laurel—that’s the sister—seems just weird.”

“Your dad asked him to help you detail?”

I nodded, pouting.

“Can you get out of it?”

“Maybe. I can try. I wish you were helping me.”

Elliot exhaled deeply. “I know. I feel bad about it, West, especially with Trudy gone. Just remember, working all summer for my dad, I should save enough to buy a car. That’ll be nice, right? We can go out whenever we want this fall, without having to track down a vehicle or bum rides off Whit.”

“True,” I said. “I just feel like I’m never going to see you.”

“You’re seeing me right now, right?” he said, propping himself up on one elbow and tucking the hair that had come loose from my ponytail behind my ear with his other hand.

“I guess. I just already know how this is gonna go: you’ll either be on the farm or in the weight room.”

“You can join me in the tractor sometime,” he offered.

“Oh, golly gee,” I teased. “Fun!”

He smiled. “Come here, you.”

Elliot slung an arm around my waist and pulled my back against his chest. He kissed me softly behind the ear, then at my jaw, then on my neck. I turned over, took his face in my hands, and kissed him on the mouth. His hands wandered underneath my shirt. “Hey now,” I warned.

He grinned against my lips. “Don’t you want to?”

I kissed him again, then sat up in his bed. “Here? With your mom upstairs? She was my sex-ed teacher, you know.”

“Maybe she can come down and give us pointers,” he teased, still lying down, his eyes dark and hooded.

I hit him in the chest. “Gross!”

I knew he wouldn’t pressure me. Even on prom night, when I’d backed out of our plans, he didn’t complain. I’d told my parents we were going to the post-prom lock-in, but instead we got a hotel room. Elliot had told me at dinner about his plans to work for his dad that summer, and that news—combined with my nerves—made me crabby and doubtful. When we’d changed out of our prom clothes and were sitting side by side on the hotel bed, I’d admitted I wasn’t ready.

Disappointed, Elliot had begun, “Do you know—?”

“Know what, Elliot?” I’d snapped, trying not to cry. “That a million other girls would consider themselves lucky to be in my situ

ation?”

He’d frowned and spat out, “God, don’t keep pushing me into that shitty jock box! You know I hate that.”

I was quiet—embarrassed and a little regretful, even though it was my decision. I didn’t even know exactly why I was backing down: something to do with timing and fear and discord and—ugh—my dad.

“West,” Elliot had said, standing up and pulling me to my feet, “listen: I’m the lucky one here.” Then he’d kissed me on the cheek, grabbed our overnight bags, held out his hand to me, and together we left the hotel and spent the rest of the night at the lock-in.

“Not tonight,” I said to him now, there in his bedroom, then leaned down to kiss his lips again. “I have to go.”

Elliot rolled his eyes. “Time for your date with Sullivan Knox?”

“Yup.”

“I hate that damn radio show,” he said, sitting up beside me.

“I know.”

“It’s so pointless.”

“It’s the opposite of pointless. It’s . . . pointful.”

We both grinned. This kind of back-and-forth was so routine it felt like reciting lines. Whenever Trudy heard us arguing over August Arms, she’d say, “You fight like an old married couple,” and Elliot would smile and I would laugh because I knew we were both thinking of “I do” beneath the monkey bars.

He teased, “Okay, fine. Radio, have fun. Detailing, no fun. Got it?”

“Deal,” I said, grinning, then ruefully added, “I already miss you.”

Elliot kissed the top of my head. “Look,” he said, “Marcy and Bridget are still around—call them up, go to the beach! Read a thousand books. Go bug Whit when he’s working at the mini-mart; make sure he’s keeping out of trouble. I’ll see you whenever I can—I’m not going anywhere.”

three

I woke up to the sound of my little brother, Shea, pitching a fit over how much sugar he could put on his cereal. “Think you could be any louder?” I complained on my way down the stairs from my bedroom.

Shea and Libby, seven and twelve, were both sitting at the breakfast bar, eating generic Cheerios, which—in Shea’s defense—taste like crap unless you add a ton of sugar. Mom was at the kitchen table, which was covered in her scrapbooking materials. The three of them look like a trio, all sandy blond and blue-eyed. But I look like my dad: eyes and hair like dark chocolate.

“Where’s Dad?” I asked, pouring some orange juice.

“Jim Roberts found out last night that he lost his job. Dad went over to talk to him,” said Mom.

“Oh. That sucks.”

“Don’t say ‘sucks,’” Mom said. “I’m sure it will all work out. ‘When the Lord closes a door, somewhere he opens a window.’”

“Is that from the Psalms?” Shea asked, milk dripping from his chin.

“It’s from The Sound of Music, moron,” said Libby.

“Libby, don’t say ‘moron.’”

Mom. She’s the prototypical pastor’s wife, a smiling martyr for God because she signed on for a life of pot roasts. She gets sort of swallowed up by my dad’s overwhelming personality: everyone in Green Lake knows and likes my father.

“How long is Dad gonna be gone?” I’d been hoping for some info before Silas arrived this morning.

“Hmmm?” Mom asked. “He’ll probably be home for lunch and then go over to his office for the afternoon.”

It felt like I was always asking when Dad would be around. If he wasn’t off visiting or consoling parishioners, then he was in his office, studying or preparing a sermon, or else counseling young couples or answering questions from the people who would drop by the church building, looking for advice or prayer. With only a handful of churches in our town, he stayed busy; meanwhile, we got the leftovers: migraine-routed Dad, needing dark, soundless rest.

Inside our house, an exhausted husband and father. Outside it, a minister in perpetual motion, Green Lake’s hero, a good man.

Mom held up a couple of pieces of nearly identical scrapbooking paper, trying to choose which was best. “Your dad mentioned Lillian Mayhew’s daughter moved into the old Griggs house and that her grandson is going to help with your detailing this summer, yeah?”

“Yep. His name is Silas. And listen up, Shea—I don’t want you bugging us when he comes over, all right?” Libby was shy and generally wary of all boys except for Chuck Justice, this teenage pop singer she was obsessed with. Shea, on the other hand, was the princeling of awkward questions. Just the other night at dinner, he’d looked up from his spaghetti and, with furrowed brow, asked, “What’s a whore?”

“Do you have two boyfriends now?” Shea asked, making faces at himself in the reflection of his spoon.

“No,” I stressed. “Seriously, Shea? Does that make any sense?”

He only shrugged.

“Just don’t bug us, okay? We’ll have plenty of work to do without having to deal with any crap from you.”

“Don’t say ‘crap,’” said Mom, choosing the light gray over the light gray. I took my OJ outside to the front steps.

Silas showed up that morning on a bike, wearing mesh shorts, Tevas, and a T-shirt that said, “South Korea has Seoul.” His thick hair was damp and had a tiny bit of curl to it. I felt a little plain with my stick-straight brown hair pulled back into a basic ponytail. Jerk or not, he looked like an adventure with skin on.

“Morning,” I said, without moving from my spot on the steps. “You look tired.”

“Vader rocked my world last night,” he joked with a wicked grin.

My first thought was multiple personality disorder.

He seemed like a different person from yesterday, more relaxed, less standoffish. His eyes—dark like an oil spill—took in everything as if he expected the things around him to make him laugh.

“So?” he asked, nodding toward the bin of cleaning supplies sitting in my driveway.

“Have you ever detailed a car before?” I asked him, standing up and joining him in the short driveway. When he shook his head, I said, “Okay, listen. I’ve been doing this for four years, and if you screw up and make me lose my customers, I . . . I don’t know what I’ll do, but it won’t be pretty. The most important thing you have to know is this: do not use a vinyl product on leather seats. Repeat after me: I will not use a vinyl product on leather seats.”

Silas put his right hand on his heart and held his left up as if he were swearing in at court: “I will not use a vinyl product on leather seats.”

“Okay, good,” I said. “Don Travers—he’s on the city council with Dad—is going to be here in a couple minutes; then you’re going to have to listen closely and work fast—but be thorough. If you do well, I’ll let you be my apprentice this summer—”

“—partner,” he interrupted.

“Apprentice,” I repeated firmly. “In which case, we make a hundred bucks a car and split it sixty-forty. A couple times, we’ll need to take a cut from the total to restock supplies. Not too shabby, is it? Of course, we do only about two or three cars a week. Makes for an easy summer.” I thought of Elliot, how he’d been up since dawn and would be every day this week.

“You split it sixty-forty with your friend too?”

“No. Trudy and I split our profits down the middle. But you are not her.”

“Thank God.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Nothing.” Silas appeared to be doing the math in his head.

I eyed him suspiciously. “What do you need a job for, anyway?” I asked. “Your family is loaded.”

He laughed, even as I clapped my hand over my mouth. “I need to get out of the house. And I buy a lot of stuff my parents think is crap,” he said. “Or maybe you think they bought my ‘Your Mom’s a Horcrux’ T-shirt?”

I stifled a laugh as Don Travers pulled his car into my driveway and parked.

Don was nearly as tall as Silas, though not as thin. “Hi, West,” he said, getting out, along with Judy, who waved at my mom through the front window. “W

e’re going to get breakfast at Mikey’s and then go run some errands. Hardware store. Red Owl. Three hours enough time, you think? We’ve got plans in St. Cloud this afternoon.”

“For sure,” I said. “Although I’ve gotta teach the new guy here the ropes.” I nodded toward Silas, who grinned and shrugged as if he were helpless. “Silas Hart,” I told Don. “He’s Arty and Lillian’s grandson.”

“No kidding!” Don said, clearly pleased. “You’re not Teresa’s son?”

“That’s me,” said Silas, still with that same grin that annoyed and excited me.

“Teresa Mayhew was a freshman my senior year. I was the captain of the track team, and I couldn’t catch her,” Don said. “I guess I thought she was in Florida.”

“For a while,” said Silas. “Alaska most recently. Now back in the motherland.”

“Can’t do better than Green Lake,” said Judy.

Don added, “You’ll catch on quick to life here.”

“I hope so, Mr. Travers. How are the cows?” By which he proved that he already was.

Silas was just as sharp at learning to detail, a star pupil. I was impressed but also sort of irritated. “We start on the inside,” I said. “Inside out. And everything has to be thorough, like I said. It’s called ‘detailing’ for a reason.”

“What are you, the dictator of detailing?”

I glared at him. “Do you want this gig or not? Because I don’t need your help, you know.”

Silas grinned. “Whatever. You just told Mr. and Mrs. Travers their car would be done in three hours. It would take you at least five on your own.”

He was right.

“Fine,” I said. “First, we take out the floor mats and vacuum like crazy. Move the seats around—”

“—does that mean you want me to stay and help?” he interrupted.

“—as much as we can to get everything. Then we wash the floor mats and clean the hard surfaces inside. We use cans of compressed air to get into the dashboard crevices, and we clean the vent grilles with Q-tips. And you already know about the seats.”

Silas crossed his arms in front of him.

Truest

Truest